To mark International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month,

we delivered a presentation for NHS Lothian’s Women’s Network to highlight the instrumental

role of two pioneering women who held very different roles but whose career

paths converged in the mid-1980s to tackle a major health crisis. The theme for

this year's IWD is #AccelerateAction and, with this in view, Dr

Helen Zealley and Dr Jacqueline Mok played an essential part in establishing a response to critical

issues that affected the health and wellbeing of the people in Lothian.

Dr Helen Zealley completed her studies in Medicine at the

University of Edinburgh. In the 1970s, she became involved with the emerging speciality

of Community Medicine, specialising in Maternal and Child Health within the

children’s service of the Edinburgh Public Health Department for 10 years. She

was appointed Director of Public Health (DPH) – also known as the Chief

Administrative Medical Officer (CAMO) – of Lothian Health Board, which later

became NHS Lothian in 1998, and Executive Director of LHB in 1991, a post she

held until her retirement. During her career, she encountered challenging

periods for Lothian Health Board, such as initiatives to combat the high rate

of HIV infection in Edinburgh and a financial crisis in the early 1990s.

As the Director of Public Health, Dr Zealley was involved,

directly or indirectly, in all the developmental aspects of Lothian Health

Board during the period. These included policies, strategic planning processes

and frameworks, service provision, operational plans, efficiency savings, and auditing…

all of which are evidenced in our archive.

LHB Smoking Policy, Promotional leaflet (GD25/1/1/1/2)

LHB Smoking Policy, 'Smoking Prevention, A Health Promotion Guide for the NHS' promotional booklet (GD25/1/1/1/2)

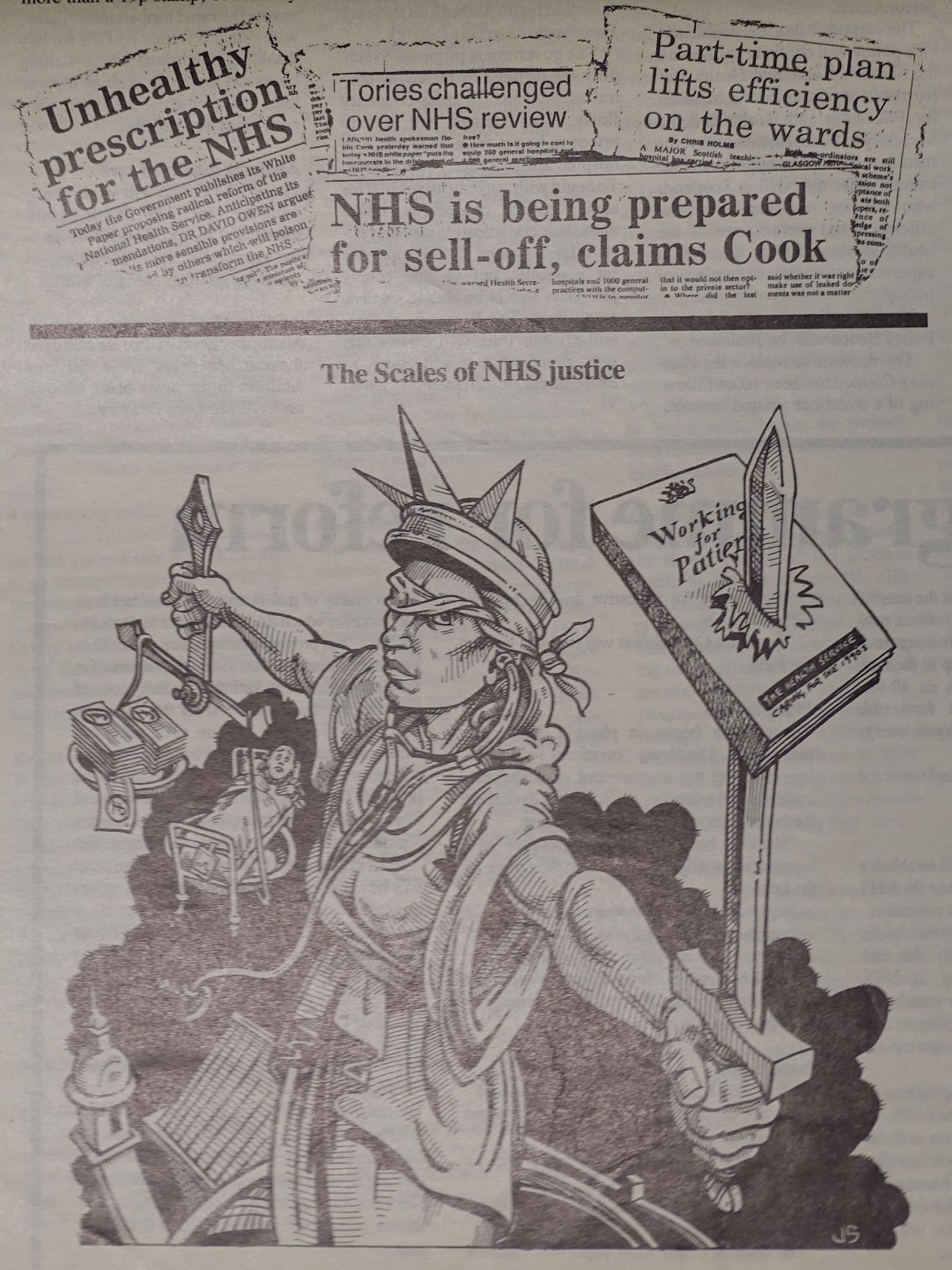

However, the hardest challenge she

had to face, at least during the first years of her tenure, was the

government’s white paper Working for patients published in January 1989.

In short, 1990 was a year of significant change and turbulence for the NHS both

nationally and locally since a new form of healthcare was established whereby

health services and long-term care were to be planned and managed as a

competitive market. Within this system, Health Boards were to assess the

“health needs” of the population for which they are responsible and place

contracts to “purchase” services to meet those needs from a range of

“providers”, both locally and on a national basis, who were responsible for the

day-to-day management of these services. NHS hospitals and clinics were also

given the opportunity to opt out of their direct management links with Health

Boards and form “self-governing trusts”.

Pamphlets like this were created as a response to the government's 1989 White Paper (GD25/1/1/1/23)

Dr Zealley was not onboard with this new form of healthcare

as the right means to achieve improved service delivery and provision within

the NHS. As she stated in a letter written to an external healthcare agency,

‘my problem is that I do not believe that the purchaser/provider split is a

useful mechanism to achieve this – and I am deeply distressed by the signs of

“competition” between our provider units amongst whom we have spent years

developing a collaborative, integrated approach so that patients receive the

most appropriate “package” of preventive, acute and rehabilitative care –

irrespective of the provider of each component’. While she expresses a clear

openness to change, she opposes the privatisation of health services. Dr

Zealley was a leader, an influential woman, and a real decision-maker. Yet,

although she held a prominent position within the structure of LHB, decisions

dictated by the higher ups, or the Tory government in this case, escaped her

control.

Excerpt from Dr Helen Zealley's letter to an external healthcare body in response to the government's White Paper (GD25/1/1/1/23)

Cartoon published in a newspaper critiquing the government's White Paper (GD25/1/1/1/23)

The reform resonated across the UK and received

substantial media coverage, leading, unsurprisingly, to major disagreement and

backlash from the Labour party. Their main claim was that the government’s

‘ideologically-driven view of healthcare as another commodity to be bought and

sold in a marketplace, rather than a public service’ sought to benefit only a

small portion of the population. While aspects such as poverty, unemployment,

poor housing, and a polluted environment are essential to determine people’s

health, the two-tier system established in the early 1990s resulted in that two

patients with the same disease living in the same street and the same

circumstances could be treated differently depending on what particular type of

doctor they happened to have. This may well give an idea of the convoluted

scenario in which Helen Zealley worked during the 1990s and how her role was

impacted by the country’s political fabric.

Cover page of The Edinburgh and Lothians Post (published on week ending Saturday, 19 October 1991) (GD25/1/1/1/23)

Page from BMA News Review (January 1990) (GD25/1/1/1/23)

A few years before this, Dr Helen Zealley joined forces with

Dr Jacqueline Mok to address the HIV/AIDS crisis affecting Edinburgh from the

mid-1980s. Originally from Malaysia, from where she came from to complete her

Medicine studies in Edinburgh, she was a Paediatric Consultant for Community

Health, Lothian Health Board, as well as a member of the Royal College of

Paediatrics and Children’s Health. Her research mostly focused on HIV and AIDS

in infants and children, with a particular focus on mother-to-child

transmissions. She worked extensively on research for HIV therapies that are

not only safe for children, but also for expectant mothers. Her research

expanded beyond HIV-infected children to include HIV-affected children.

That is, children whose mothers were HIV positive. Dr Mok started a clinic for

HIV-infected children at the City Hospital in the mid-1980s, the first of its

kind in the UK. The clinic moved from this space and was granted use of Ward 8

(Ward for Infectious Diseases) at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children.

In October 1985, she was asked by Dr Helen Zealley to look

after children born to women with HIV infection. At this time, Edinburgh was

the first city in the UK to recognise that HIV could affect the non-gay

community and that it was drug use that resulted in heterosexual spread; a

third of drug users being young women of reproductive age. The uniqueness of

Edinburgh in comparison to other places was that many young heterosexual men

and women were HIV positive, but not ill.

Reducing Mother to Child Transmission of HIV Infection in the United Kingdom, April 1998 (GD59/1/2/3/2)

Dr Mok travelled to New York, New Jersey, and Miami to learn

about the services that had been set up in these places, which were described

as paediatric AIDS by Dr Arye Rubinstein in 1983. He established that

transmission of AIDS can occur in utero and published his findings in 1986.

After her trip, Dr Mok acknowledged that the HIV/AIDS programme in Edinburgh

could benefit from her respiratory background since many children would present

with pneumocystis.

The first reports of paediatric AIDS in 1983 talked about an

acute life-threatening illness with a high level of mortality. When they

eventually got that link of mother-to-child transmission, it was thought to be

as high as 50% to 80%. It was almost certain that if you had a mother with HIV,

you were likely to be infected, and then if you were infected, you would be

dead within the first 5 years of life. However, paediatric AIDS turned out to

be a long-term condition and not every child was going to be infected. The

transmission rate they found from mother-to-child was less than 10%. And from

those children with HIV in Edinburgh, many of them were very well, even before

the days of antiretroviral therapy.

On the other hand, Jacqui encountered some adversity within

NHS staff. When she was asked to set up a clinic for these children, a

colleague told her, “Well, I hope you don’t share their cups with them,

Jacqui!”, whereas somebody else asked her to keep the clinic at City Hospital

as opposed to Sick Kids, where she was based at the time. This gives an idea of

the high level of anxiety experienced by everyone. It was all doom and gloom.

Nothing was known about transmission, which could be relatable to those who

didn’t live through this crisis, but experienced the Covid-19 pandemic.

Community Child Health Research Report (GD59/1/1/5)

At the time of establishing

this clinic at City Hospital, there was only one Ward for Children and all

paediatric trainees were at Sick Kids with no rotation into City Hospital. Dr

Mok would be called because they had no junior doctors who could assess the

children. To exemplify, if they needed an intravenous infusion, she had to go

and do it herself because the trainees were adult-trained. As for her team, it

consisted of Dr Mok (half time), an MRC- funded research fellow for 3 years who

was then replaced by a trainee, a paediatric trainee, a full-time health

visitor, and a secretary working 17.5h. They were eventually joined by an

obstetrician and a specialised midwife as well.

In 1989, she attended her first HIV international conference

and as a result of meeting other paediatricians and epidemiologists, they

started the European Collaborative Study (ECS), for mother-to-child

transmission of HIV. In its hayday, Dr Mok received referrals from Edinburgh

and the Lothian, Fife, Tayside, the Borders, the Highlands and Islands, and

even northern England.

The Public Health Challenge, Outline Programme (GD25/1/2/2/2)

Excerpt from The Public Health Challenge, Outline Programme (GD25/1/2/2/2)

In the early days of the European Collaborative Study, she

was always having to justify herself every time she was asked, “You’ve only got

150 children, why are you needing so much time?”. However, each child needed

follow-up at one week, three weeks, six weeks, and then six-weekly until six

months, three monthly until aged 2 years, and then six to twelve monthly. The

reason for this was that they were looking for signs of infection.

They also had to speak to the mothers in the ante-natal

period to seek their consent and explain the purpose of the study, and they all

were very thankful that somebody was interested in them and their

children. Our colleague, Louise Williams, who’s Archivist at LHSA, did an oral

history interview with Jacquie Mok and Helen Zealley in 2018. In the interview,

Dr Mok recalls that when women ‘were recognised to have HIV during labour,

people would come into their rooms dressed in what they call “space-suits”, and

then auxiliaries would open their door, put their meals in and then shut the

door and run off’. Likewise, Dr Zealley confessed that it was ‘understandable

that there was fear and there was a lot of blood and a lot of unknown’.

AIDS Guidelines for Social Work Personnel, December 1985 (GD59/3/2/2)

We often think of the role of medical staff from a clinical

perspective. But, while Dr Mok was facing an unprecedented challenge, other

associated challenges added pressure to her role: the human element. Jacqui ran

community-based sessions. This means she didn’t wait sitting in her clinic for

parents to show up. She proactively visited households to examine her patients

and this involved encountering all sorts of situations. She recalls that

mothers were always grateful for her visits and would comply with anything she

asked from them. Many of these women were on their own, whereas, in other

instances, Dr Mok would see a man in the house and assume he was the father

without asking any questions. Fathers may or may not join their partners for

the visit. It was rather common that they left the room during the

blood-letting as they couldn’t stand seeing how the medical staff inflicted

pain on the baby by putting a needle into their veins. Likewise, there were

cases when they ended up shouting at her after trying to extract their baby’s

blood several times.

The Sunday Times - "Born survivor", 15 February 1998 (GD59/1/2/1/2)

The Sunday Times - "Learning to live with the HIV virus", 15 February 1998. The page displays a photograph of Dr Jacqueline Mok (GD59/1/2/1/2)

Many of the mothers saw the birth of their child as an

opportunity to stop using drugs, although there would still be mums who would

continue to use them. At the time of the visit, Dr Mok wouldn’t know what state

they would be in. They could be awake, or not, and there was no way to tell

whether they would cooperate.

In those cases where women were deemed unfit to be parents

due to their ongoing use of drugs, Dr Mok had to work with social workers and

foster carers. For this purpose, she ran special training sessions to educate

them about the needs of infected children and the risks they presented to their

families. Some of these children ended up going to school and because of

confidentiality, Dr Mok’s team didn’t disclose that a child was HIV-positive

and, by extension, that the mother was positive too. Instead, they implemented

a universal management of children who could be infected approach to every

school and nursery, which was a success.

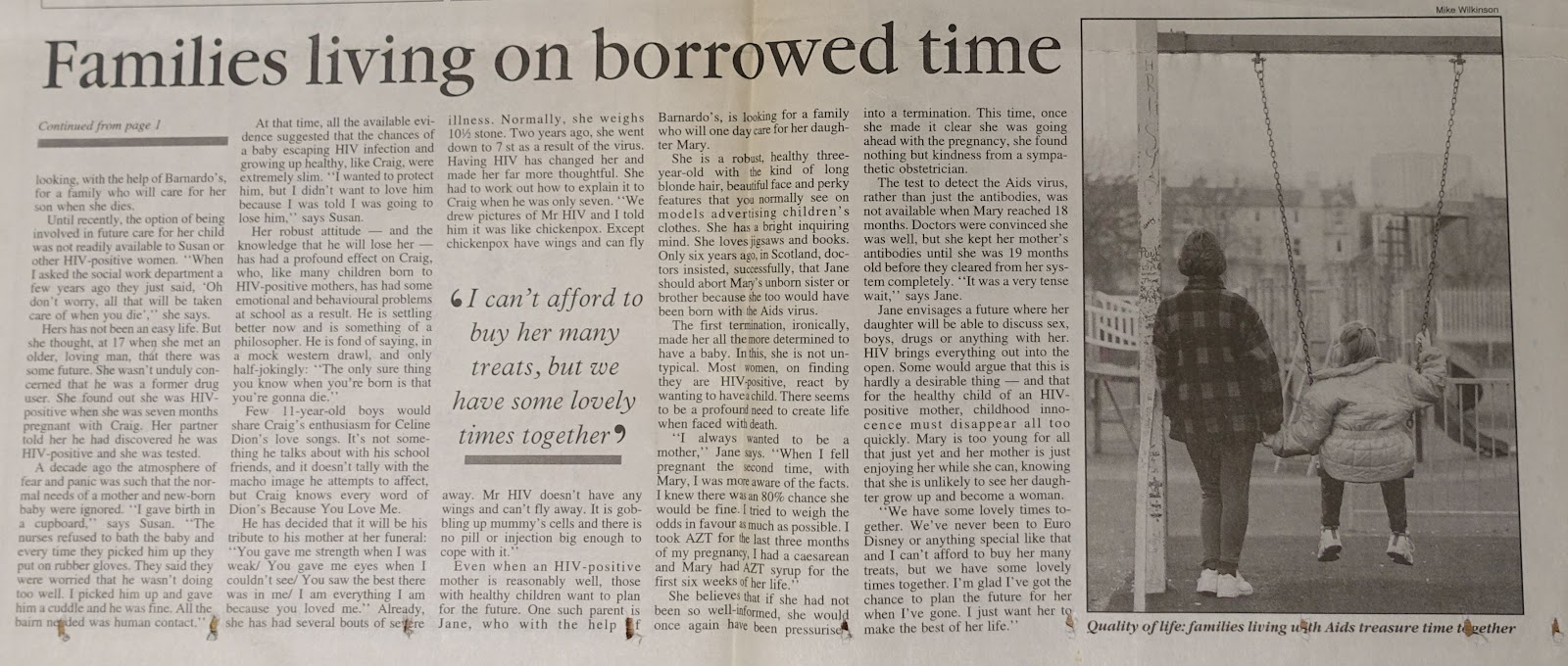

The case of Aileen Ballyntine received plenty of media

attention and made Dr Mok realise that they might have more children affected

by HIV rather than infected by HIV. Ten years down the line HIV-infected

parents were getting ill, before antiretroviral therapy, and they would develop

pneumocystis or suffer from encephalitis. Disclosing their secret to their

children was a very sensitive thing for the mothers to cope with. A lot of

these women, because of their drug use, didn’t have a support network and had

distanced themselves from their families. They lived dysfunctional lives and

were very unsupported. Others would have parents who rejected them. A ‘you

brought it on yourself’ kind of situation. Some grandparents took care of the

children instead of having them become fostered or adopted. In this scenario,

many children born to HIV-positive mothers had behavioural problems, in

particular during their adolescence, as this seemed to be the time when many of

them found out their mum was going to die.

The Sunday Times - "Letting go of mum", 15 February 1998 (GD59/1/2/1/3)

The Sunday Times - "Families living on borrowed time", 15 February 1998 (GD59/1/2/1/3)

In the oral history interview, Dr Mok remembers one

particular case of a child who turned out not to have HIV. The grandfather was

desperately trying to do everything right for his granddaughter, feeling they

had failed their daughter in the past and were trying to make amends. His wife

became very ill and he brought the little girl to Dr Mok since he couldn’t take

care of simple things such as giving her food because he couldn’t cook. He had

relied on his wife all his life to raise their children and now felt powerless.

In other cases, parents could not gather the courage to explain to their

children why they were having their blood taken over the years and asked Dr Mok

to speak to them. There is even a mention of a case when the father wanted to

find and kill the person who gave his wife HIV after she was diagnosed with it.

Dr Mok wore many hats. She was an HIV-specialist doctor, a counsellor, a social

worker…

The mothers’ social spectrum remained a constant during

these years. Unless children were fostered or adopted (this would be by more

structured families), children would grow up within a disadvantaged and

dysfunctional family system. It was in areas like Craigmillar, Niddrie,

Muirhouse, Pilton, and Leith where HIV hit hard. We may think of Leith, for

instance, as this trendy part of Edinburgh nowadays. A place with a lively

cultural scene and full of nice cafes, bars, and restaurants. However, the

reality was way different during the mid-1980s and early 1990s. Think of Trainspotting.

Some of the children from Dr Mok’s cohort became mothers

themselves and coped with varying levels of success. Many mothers continued to

lead an equally dysfunctional life and parenthood didn’t change that. Many of

them are part of a cycle, or a loop, that goes round and round as that’s how

their children are raised. They know no different and follow what their mothers

say and do. Just like any other kid. But, to conclude on a positive note, Dr

Mok stated that those cases who managed to break the cycle of deprivation

managed to do well for themselves.

.TIF)

.TIF)