If you follow

social media from our colleagues in the Centre for Research Collections (CRC),

you may know Skills for the Future trainee, Paul Fleming,

who’s with the CRC until mid-autumn on a programme to expand his experience and

knowledge of roles in heritage institutions. Well, Paul is currently spending

some time at LHSA working with medical collections and in this week’s blog, he

tells us about himself, how he first came into contact with LHSA and tells us about the Skills

for the Future programme:

My first

experience with LHSA came in the form of a

series of practical seminars during my third year as a history student at the

University of Edinburgh. I did not stumble onto this course by accident, or

just because I had to pick something: I had been taking a one year course called

Madness and Society which I found highly interesting and fascinating and through

this I developed a passion for medical history and the richness of the original

sources which the field had to offer. So naturally, when the chance came up to

work with LHSA’s archival materials and one of their archivists it was my first

choice for the third year course History in Practice.

However, at the

time I was simply excited about getting to see some of LHSA’s vast collection

and did not foresee the impact that this would have on my life and future

career. I became truly inspired by the archive and the role of the archivist.

When studying history there is one question you are frequently asked by

friends, family and people you meet – “what are you going to do with a history

degree, become a teacher?” To be fair, I had no real idea what I was going to

do to start with as I was simply enjoying learning and developing the set of

skills needed for history. But that changed after my seminars with LHSA: I now found

myself responding to that almost rhythmically frequent question – “I quite

fancy a career in archives”.

Now… this

stared to throw up all sorts of different assumptions as friends pictured me as

some sort of Gandalfesque figure stalking some deep dark cavernous basement,

battling through giant cobwebs with lantern in hand – coughing and spluttering

as dust is disrupted from its slumber on some ancient scroll. As appealing as

that actually sounds to me, I knew from my time at university that the

perception of archives doesn’t always match the reality. The Centre for

Research Collections (CRC), where LHSA is based, is a refreshingly bright space

with spectacular views of the city of Edinburgh and the surrounding hills, as

it sits not in the basement but on the top two floors of the University’s main

library.

CRC offices on the top floors of the George Square library.

My time as a

student with LHSA also gave me ammunition to fight the perception of the

archivist as some sort of solitary figure, cut off from the rest of the world

with nothing but old manuscripts to turn to for companionship. Nothing could be

further from the truth in the modern age. If it wasn’t for the archivists willingness

to engage, (be it with students, researchers, or the wider public) then I would

not have been inspired to travel the path which I now find myself on. Outreach,

advocacy and education are becoming just as important as cataloguing and

dealing with enquiries. Not only do they challenge some of the assumptions

mentioned above, such programmes are also highly valuable for demonstrating the

importance and value of archives for our cultures and societies – especially

during times like these when funding is a rare beast to find. Fundamentally,

for me anyway, I feel that archives are about stories and what good is a story

if it is never shared?

So what happened

next? Well… after graduating last year I found out about the brilliant Skills

for the Future project (courtesy of a lovely archivist I met whilst camping in

the Highlands) which is run by the Scottish Council on Archives (SCA). This

gives six trainees each year, for three years, the chance to work and gain

valuable experience in archives throughout Scotland. This on its own seemed like a brilliant opportunity for someone like me to break into the

sector. However, the fact that there was a traineeship positon at the CRC,

where my passion for archives was born, I knew it was the one I had to go for.

When I was told that I was the successful candidate I literally jumped for joy,

but still found it hard to believe that I would be working in the same place

that I had been a student.Paul working on the Laing collection in the CRC stores. Not a cobweb in sight...

I am now almost nine months into my traineeship and I have had some wonderful experiences. These include being involved in the Explore your Archive social media campaign; planning and running school workshops for the Widening Participation project; and cataloguing some of the University of Edinburgh’s David Laing collection (in which you can discover absolute treasures every time you open a box). However, on a more personal level, getting the chance to spend two months working for LHSA cataloguing the neurosurgeon Norman Dott’s case notes has been truly remarkable – and pretty surreal to be sitting on the other side of the wall to the seminar room where my old workshops were held. I always did wonder what it looked like on the other side - well now I know.

(To be

continued...)

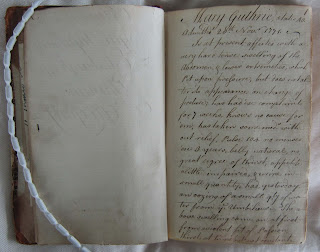

Paul hard at work at LHSA with Norman Dott's case notes...