Lauren writes about a much beloved nurse and the state of nursing before the implementation of the 'New System of Nursing'.

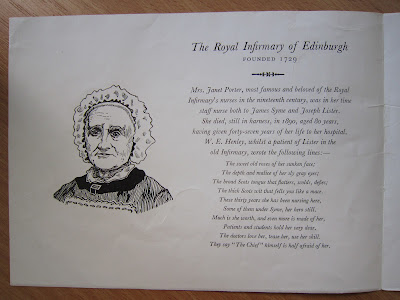

August 12th marked the anniversary of Florence Nightingale’s death. Having a particular interest in the history of nursing, and being in the unique and privileged position of having immediate access to the archives, I took the opportunity to investigate the state of nursing at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (RIE) before the introduction of the Nightingale nurses and the training school for nurses. I came across several mentions of a Mrs Janet Porter, a staff nurse at the RIE for a total of 47 years. She lived through the incredible changes which took place at the RIE in 1870s with the introduction of the ‘New System of Nursing’.

|

Dr Joseph Bell painted a rather bleak picture of nursing before the introduction of the Nurses’ Training School: 'Without apparent exaggeration, it is almost impossible to convey to this generation the depths of disgraceful ignorance and neglect in which nursing lay in hospitals in 1854.'

There were nine nurses total in the surgical wards which housed 72 patients. These nine women were-'two staff nurses, each with about thirty six beds to look after, and seven so-called night nurses who had also to do the scrubbing and cleaning of the wards and passages.'

|

| Joseph Bell (1837-1911) was a Scottish surgeon and advocate for the training of nurses. |

Bell’s description of the staff nurses Mrs Porter and Mrs Lambert is rather flattering: 'wonderful women of great natural ability and strong Scottish sense and capacity, of immense experience and great kindliness. Up to their strength and opportunity, probably no two finer specimens of the old-school nurse could be found. All honour to their pluck and shrewdness!'

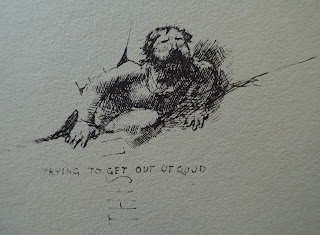

But he spares no punches when describing the other seven nurses: '…poor old useless drudges, half-charwoman, half field worker, rarely keeping their places for any length of time, absolutely ignorant almost invariably drunken, sometimes deaf, occasionally fatuous—these had to take charge if our operation cases when the staff nurses went off duty. Poor creatures, they had a hard life!'.

I had done some research on nursing for the digital resource list on the history nursing and one of the first things I learnt was that the general perception of nurses during the 18th and better half of the 19th century was incredibly negative. Figures like the fictional nurse Sarah Gamp from the Dicken’s novel Martin Chuzzlewit perpetuated the untrained, incompetent and drunk stereotype of the Victorian nurse. The RIE minute books (Nov 1967-Nov 1869 and Nov 1869-May 1871) confirm that there were instances where nurses were caught intoxicated on the job, and there were quite a few complaints made in regards to the general conduct of the nurses.

|

| A dishevelled nurse with her disgruntled patient. Coloured lithograph by W. Hunt. c. 1825. Credit: Wellcome Collection. |

|

| "The Nurse"; anonymous. Credit: Wellcome Collection |

Angelique Lucille Pringle was the second Lady Superintendent of nurses. Trained at St Thomas', she was widely considered to be Florence Nightingale’s favourite. LHSA holds Angelique Pringle’s diary from 17th to 23rd Nov 1872, which she kept during a visit to the RIE while Elizabeth Barclay was Lady Superintendent. It is an invaluable record which vividly captures both the state of nursing at the time and the tensions and prejudices between these new, highly trained and educated nurses and the ‘old school nurses’.

Pringle makes mention of nurses being intoxicated. In one instance, a night nurse called Annie Fisher is caught asleep on the job. After many attempts to wake the nurse up, Mrs Barclay asks Fisher “what about your patients, nurse?” Laughing, Fisher replies “Oh, I had nae mind o’ them”, which Pringle writes is a 'skillful epitome of the state of nursing'. After Pringle and Barclay wake up a Day Nurse to take charge of the ward, Annie Fisher follows the two women, enraged and screaming that she “had seen a good many out and she would see us out too!”

|

| Typescript copy of Miss Pringle’s Diary LHB1/112/2 |

|

| RIE Minute Book LHB1/1/24- complaint regarding the conduct of Syme's night nurse, mention that she "has been indulging in intoxicants". |

|

| RIE Minute Book LHB1/1/25- report of nurse Janet Houston who had "been found intoxicated and unfit for duty" |

|

| RIE Minute Book LHB1/1/25- nurse Jane Riddoch had been found in a state of intoxication |

Much like Bell, Pringle lays it on pretty thick with her description of the nurses and her comments are often cruel and ignorant by today’s standard: 'Two of these nurses were hideously deformed in face, quite unsuitable on that account alone for their post. Their wards looked nice however.' The classism is so abundant within her descriptions of the nurses that it’s a bit hard to stomach at times- 'These were very pale all of them, some were sodden, some were stupid old women, some slovenly young ones of the lowest class.'

|

| LHB1/1/25 RIE Minute Book, complaint of nurses diet. |

Angelique Pringle mentions Mrs Porter a couple of times in her diary: 'One head nurse, Mrs Porter, looked quite a dear old lady but her wards were not nice. She has been 27 years here and has now one of the heaviest charges.'

|

| LHB1/112/1 Angelique Pringle's diary |

Before the introduction of the New System, it would appear that unruliness and chaos were not uncommon in the wards of the Infirmary. It also seemed to be pretty normal for nurses to be dismissed: 'On asking the nurses their length of service, we found several who had been only two days in the house ‘since that night’ said one of them ‘when so many of the nurses got drunk’.'

Even Mrs Porter’s conduct, according to Angelique’s diary, did not seem to comply with the Nightingale model of cleanliness and order: 'We found nearly all the gas blazing, the day nurses running about and a perfect riot of laughing and talking going on among the nurses and patients. Nurse Porter’s wards were the noisiest, the old lady herself being very loud.' Although she isn’t exactly reverential about the “old lady”, she does seem to acknowledge a certain ‘spark’ that seems to have captivated so many people.

Even Florence Nightingale herself wrote a letter to Angelique in which she expresses a fondness for nurse Porter:

'Please give her my kindest Christmas wishes and tell her I remember her perfectly and her care of me 16 years ago when Mr Syme took me over the infirmary. How long ago!'

|

| Nightingale's letter to Pringle. LHB1/111/3a |

Another interesting record is 'Biographical notes on Nurses not trained under the new system here, on duty Sep 1887': 'Dear old Mrs Porter, the crown of the staff, who needs no other description.'

|

| LHB1/112/9 Notes on early nurses- nurse Porter is described as 'the crown of the staff' |

Mrs Porter provided inspiration for the poet W E Henley who was a patient of Joseph Lister at the Royal Infirmary from 1873 for three years. He wrote the following poem about Porter titled ‘Staff Nurse- Old Style’:

THE greater masters of the commonplace,

REMBRANDT and good SIR WALTER — only these

Could paint her all to you: experienced ease

And antique liveliness and ponderous grace;

The sweet old roses of her sunken face;

The depth and malice of her sly, grey eyes;

The broad Scots tongue that flatters, scolds, defies,

The thick Scots wit that fells you like a mace.

These thirty years has she been nursing here,

Some of them under SYME, her hero still.

Much is she worth, and even more is made of her.

Patients and students hold her very dear.

The doctors love her, tease her, use her skill.

They say ' The Chief' himself is half-afraid of her.

|

| GD1/8/2 Pamphlet, 1957 |

Henley was a patient during a time of great change at the RIE, when the structure and training of nurses was undergoing a historic transformation. He immortalised these sharp contrasts of the ‘Old Style’ and ‘New Style’ nurse (as he would coin them), in his poems. This one is called ‘Staff-Nurse: New Style’-

BLUE-EYED and bright of face but waning fast

Into the sere of virginal decay,

I view her as she enters, day by day,

As a sweet sunset almost overpast.

Kindly and calm, patrician to the last,

Superbly falls her gown of sober gray,

And on her chignon’s elegant array

The plainest cap is somehow touched with caste.

She talks BEETHOVEN; frowns disapprobation

At BALZAC’S name, sighs it at ‘poor GEORGE SAND’S’;

Knows that she has exceeding pretty hands;

Speaks Latin with a right accentuation;

And gives at need (as one who understands)

Draught, counsel, diagnosis, exhortation.

Here, we can see the marked differences between the two nurses, the 'New Style' nurse is represented as a more educated and ‘genteel’ woman.

|

| Photograph of Janet Porter (middle) c.1870 |

|

| P/PL1/S/257 Photograph of Angelique Lucille Pringle, with a group of senior nursing staff c.1880 |

I find it incredible and quite moving how cherished Janet Porter was. She was neither an innovator nor was she a reformer but she seemed to have made a deep impression on those around her. Who says that one has to be a trail-blazer in order to deserve recognition, poems and portraits?

She certainly seemed deserving of recognition- her care no doubt changed many patients' lives. Nurse Porter was clearly very good at her job, although untrained to the degree of the Nightingale nurses, she gives me the impression of having been hard-working and committed to building relationships with those around her- staff, students, patients and professors alike. The fact that she was kept on even after the introduction of the training school is evidence of that. She was an exemplary nurse at a time when nursing was vastly underappreciated and nurses were regarded with distrust.

Janet Porter was Lister's staff nurse from 1869 to 1877. When the new RIE opened in 1879, she was kept on in the position of a "retainer" rather than an active nurse. She died in 1890 at the age of 80. A bed in Ward 9 was named the Janet Porter Bed and her portrait, subscribed for by the nurses who had been associated with her and presented to the managers in 1890, was hung in the main corridor of the surgical hospital in the vicinity of the ward.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

%20Encl..JPG)

%20Encl..JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)