Our latest blog comes from Carly Davidson, who's been working with us on an internship to make over 100 letters written by Royal Edinburgh Hospital patients accessible to readers through rehousing and listing. Whilst you can visit us and see the hundreds of letters written by patients that were previously kept with their case records, these particular ones (collected separately by the heads of the hospital) need some TLC before they can be used by researchers!

Hello, I’m Carly and I joined the LHSA team at the end of

October as the new archive intern. Prior to starting my internship, I recently

completed a MSc in Information Management & Preservation at the University

of Glasgow back in August, where my interest in indexing records motivated me

to apply for this internship. I’m excited to be able to put some of the skills

I learnt to use and to gain practical experience working on such an interesting

project.

For the duration of my internship, I will be working on an

indexing and rehousing project for two boxes of patient letters from GD16, the

collection of the Physician Superintendents of the Royal Edinburgh Hospital

(REH), then known as the Royal Edinburgh Asylum. While the letters are varied

in sender and content, most of them are addressed to Doctor Thomas Clouston,

the Physician Superintendent of the REH from 1873 to 1908, with most of the

letters being written within that time frame. Many of the patients were writing

to Doctor Clouston to express their discontent both at their treatment and their

being held within an asylum. For patients whose letters were not intended for

Doctor Clouston, their letters were held back as the 1866 Lunacy (Scotland) Act

permitted medical personnel to intercept and retain patient letters,

particularly patient letters which were critical of life in asylums and those

which indicated the severe condition of patients’ symptoms.

Indeed, critiques of asylum life are commonly found in the

GD16 patient letters, with patients expressing discontent at their diagnosis,

their treatment in the REH, and the living conditions they were experiencing. In

one letter titled ‘A list of 31 ‘Ideas for an Asylum for the insane’’,

suggestions were made to improve conditions within the hospital, and all other

such institutions, with ideas ranging from the provision of a ‘Library of

well-chosen books’ to a recommendation that ‘A few docile quiet cats to be kept

as pets for the patients.’ Not all of the content is critical, with other

letters being written to family and friends, and some acting as evidence of

patients’ more severe symptoms, such as the experience of religious delusions

prompting a patient to write letters discussing the divine orders they have

received. Such letters can prove more challenging to read, with words and

sentences often disjointed or incomprehensible.

The first stage of the project has involved reading and scoping

the letters to identify information for use in indexing, such as names or

dates. The content of the letters proved challenging, not only for the

sensitive nature of the letters, but for the challenges presented in

identifying necessary information. With most of the letters being from the 19th

century, identifying information required strong palaeography skills and the

ability to interpret text which was not always clear. Adding to the confusion,

some of the letters had already been labelled with information about patients’

names, but this legacy information did not always correlate to the content of

the letters, meaning additional research was required to link the letters to

patients of the REH.

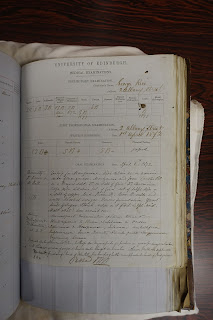

One such example of this comes in the form of a notebook

which was previously labelled as belonging to ‘AJA Dick’ - a name which does

not exist in LHSA's database of REH patients. This name, while incorrect, was

interpreted from a small signature in the notebook, from which I could only

clearly make out the initial ‘M’ and the surname ‘Dick’ which only slightly

narrowed down results from the database. As the letters are some of the oldest

records I’ve worked with, my palaeography skills and understanding of cursive

could only lead me so far in identifying names, and I was dependent on

recognising other contextual information in the text to identify the patient

themselves. This involved looking for any notes of the patient’s condition, the

date of their admission, or personal information concerning places or family

members.

The first picture shows the front of the notebook

mislabelled as belonging to AJA Dick. Below, a picture

of the inside cover of the notebook shows a signature and an address in

Kelvinside, Glasgow. The signature was later identified as being Maggie Dick, short

for Margaret Dick.

After a few attempts at deciphering the handwriting, and

with the help of Louise Williams the LHSA archivist, the signature in the

notebook gradually became clear as belonging to Maggie Dick, though this did

not result in an exact hit when searched on the REH database. Rather, using

context clues in the text itself, such as the frequent mentions of a specific

Glasgow address, allowed the notebook to be identified as belonging to Margaret

Dick. While Maggie’s writing is the main feature of the notebook, recounting

stories of the other patients and her life back in Glasgow, the notebook is

also embellished throughout with small sketches which illustrate Maggie’s

words. Other letters similarly include artwork, ranging from artworks done by

the patients themselves to illustrations and images torn from books. A small

number of materials included in the collection are not letters at all, taking

the form of works of poetry and small plays or stories. These items have been

particularly interesting to look through, with small works of art or poetry

adding a very personal touch to a letter in a way which still resonates today.

Images showing two of the sketches from Maggie’s notebook, one depicting two small flowers, and the second a small doodle of her mother.

With the scoping stage of the project now completed, the

next stages will see that letters are rehoused into suitable archival

materials, and made accessible through the creation of catalogue entries on

ArchivesSpace, a public database of archival records held here at the University of Edinburgh.

%20Norman%20Dott.jpg)

%20Davrick%20Dunlop.jpg)

%20Dr.%20G%20Jamiason.jpg)

%20detail.jpg)