In this week's blog, Archivist Louise learns how 'auld reekie' cleaned up from LHSA's public health collections:

You may have seen our recent social media promotion of a

very special event

at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh on 21st October

celebrating 150 years of the ground-breaking 1865 work, Report on the Sanitary

Conditions of Edinburgh, by the city’s first Medical Officer of Health,

Henry Duncan Littlejohn (1826 – 1914). Ruth (LHSA Manager) and I are going

along to the symposium, not only because the content will be fascinating and

deals directly with our work, but also because we’re raiding the LHSA stores to

take along some items for the afternoon to bring the history of public health

in our city alive.

The symposium programme begins with a talk on the history of

the development of public health in Edinburgh since Littlejohn’s 1865 report,

followed by an account of the current health of the city delivered by NHS

Lothian Director of Public Health, Professor Alison McCallum. The day finishes

by discussing the legacy of Littlejohn’s work, and whether in 2165 (150 years

from now), we will continue to capitalise on Littlejohn’s innovative legacy.

Luckily for everyone, I’m not a doctor, so cannot help with the

city’s current ills, and I definitely can’t see into the future, but I can help

to shed light on the history of public health changes in Edinburgh through LHSA

collections. We’re taking along items that span the period from Littlejohn’s

time until the developments in healthcare with the coming of the NHS, including

images of nurseries and the school medical service in the 1940s, a letter-book

describing insanitary houses in Leith in the early twentieth century and

mementoes and memories of Littlejohn as a lecturer at the University of

Edinburgh Medical School (Littlejohn was appointed to the Chair of Medical

Jurisprudence at the University in 1897).

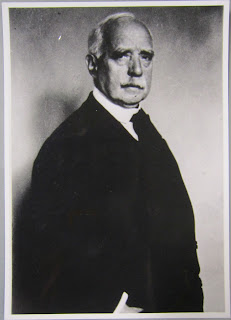

Henry Duncan Littlejohn was appointed Medical Officer of

Health for the city in 1862, a post that he occupied until 1908. Born in Leith

Street and educated at the University of Edinburgh Medical School (from which

he graduated in 1847), Littlejohn was appointed as the city’s Police Surgeon in

1854. Littlejohn’s career developed as

he lectured at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and appeared in the

judiciary courts as a crown medical examiner. However the November 1861 tragedy

in the High Street in which a tenement collapsed killing 35 people brought

Edinburgh’s appalling housing and sanitary conditions for the poor into sharp

relief. The Town Council put the appointment of a Medical Officer of Health to

the vote and, by the narrowest of margins (only one vote), Littlejohn and his

department began to transform birth, life and death in our city.

My favourite item from those I’ve chosen for the display is

the Report on the Evolution and

Development of Public Health in the City of Edinburgh from 1865 to 1919

(LHB16/2/1). Admittedly a bit of a mouthful, the report by John F Young details

the progress in making Edinburgh a cleaner, happier and healthier city

since Littlejohn’s 1865 report. Report on the Sanitary Conditions of Edinburgh

was the result of painstaking work by Littlejohn and his sole clerk. It was based

on data that they collected in 1863 on death rates, disease and housing

conditions in 19 districts that Littlejohn defined in Edinburgh. The report also

included recommendations on steps that could be taken to improve the poorest

areas of the city, such as decreasing overcrowding, lowering the height of

tenements, improving existing housing and creating space for more sanitary new

houses and streets.

The Report on the

Evolution and Development of Public Health in the City of Edinburgh from 1865

to 1919 takes a ‘then-and –now’ approach, comparing the conditions and

immediate improvements made in the late nineteenth century with life for

Edinburgh’s residents in 1919:

The first pages of Young's report comparing the nineteenth century conditions for those with infectious diseases in Canongate Poorhouse to the green fields and (then!) modern facilities at the City Hospital, opened with Littlejohn's help in 1903 (LHB16/2/1).

Young recounts the dire conditions described in Littlejohn’s

1863 research, such as a tenement called Middle Mealmarket without sink or WC

yet housing 248 individuals, and that Edinburgh had 171 cow-byres located directly below human

dwellings. He also traces the development of Edinburgh’s sanitary and living

condition since Littlejohn’s appointment, particularly listing the legislation

which came as a result of his work, such as the 1867 City Improvement Act (a

slum clearance scheme), the 1889 Notification of Diseases Act (particularly

important in being able to trace the impact of infectious diseases such as TB) and

the City Act of 1891 which empowered authorities to removed healthy people from

infected houses.

Indoor and outdoor case for TB patients at the City Hospital (LHB16/2/1).

The 1919 Report on the

Evolution and Development of Public Health in the City of Edinburgh shows

the growth of the Public Health Department from Littlejohn and his clerk in

1862 to a range of functions, including a public health group, a tuberculosis

group (comprising infectious disease dispensaries, disinfecting stations and

hospitals), food and drugs inspectors, a sanitary department, a VD scheme, a

veterinary department (checking the conditions of animal husbandry and

slaughter) and a child welfare department. Young’s report was written just as

Edinburgh’s pioneering Maternity and Child Welfare Scheme was developed (on

which I’ll be writing another blog shortly), a system of care prompted by the

number of infant deaths attributed to premature birth and nursing conditions.

This scheme was developed under Edinburgh’s second Medical Officer of Health, Dr

A Maxwell Williamson, and the necessity of its foundation makes up a large

section of Young’s survey:

Table showing deaths of children under five in Edinburgh by area, 1911 - 1915 (LHB16/2/1).

LHSA does not hold a physical copy of Littlejohn’s Report on the Sanitary Conditions of

Edinburgh (although you can read a digitised copy here),

but we do have an impressive collection from the Public Health Department.

The collection covers Medical Officer of Health reports, photographs, as well

as documents covering the main roles of the Public Health Department in

sanitation, prevention of disease, housing and child welfare. Its potential as

a research resource is huge. In fact, it’s currently a major source for a

University of Edinburgh contribution to a collaborative public health research

project, using the collection to map the lives of those born in Lothian in

1936.

There are still a few free tickets left for the 21st October Symposium on public health's history, present and future in Edinburgh, which you can sign up for here - so come and visit us to see some of LHSA's collections!

Public health on the move: a motorised ambulance and a disinfecting van in early twentieth century Edinburgh (LHB16/2/1).