Hello! I’m Judith and I’ve recently

joined the LHSA team as a conservation intern. I’ve moved to Edinburgh for 8

weeks from Newcastle, where I recently completed a two-year MA in conservation of

works of art on paper at Northumbria University. During my internship I will

be working with a range of material from the archive, including photographic

materials, architectural plans and bound volumes, as well as rehousing several

collections. This is my first real foray into a large archive and the past two

weeks have been an eye-opener!

In preparation for rehousing, together

with Claire (LHSA archive intern) I have been surveying the collection of medical

illustrations, demonstration boards, sketches and photographs generated through

the practice of the great Edinburgh neurosurgeon, Professor Norman Dott (1897-1973).

Dott emphasised the importance of good medical illustration and used

professional medical artists to document his work and publications. Medical

artists were held in high regard during this period; in more recently years

this has largely been superseded by photography. Amongst the fascinating range of illustrations in the

archive are 70 carbon dust drawings of clinical procedures. Having never

come across drawings like these before I thought I would share some of what I

have been discovering.

Pioneered in the early 1900s by Max Brödel (1870-1941), medical artist

at the John Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, carbon dust drawing was used to produce clinical images representing

anatomical detail. The technique allows for a wide variation

in tone, shading and highlights, to display a range of textures, making grey-scale, tonal illustrations look like living tissue.

In the early twentieth century the Philadelphia lithographer

Charles J. Ross invented Ross Board, which was a board consisting of a paper or

cardboard substrate with a thin layer of approximately 1/32 of an inch of finely ground

white chalk (often gypsum) mixed with a binder. The chalk mixture was applied

to the cardboard under pressure. To produce a

drawing, typically an artist makes a preliminary drawing on paper using a

carbon pencil, which is then reversed and traced onto a second sheet. This

second sheet is placed face down on the board and the image outline transferred

to the board by carefully rubbing along the lines using a flat tool or thumb nail. This ‘double transfer’ method leaves an outline

image to which tone, shading and depth can be then added by brushing on thin

layers of fine carbon powder. Layers of powder can be built up to produce

detail or rubbed away to give highlights, and coloured details can be added in pencil

or ink.

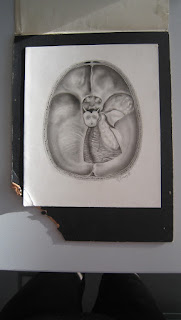

|

| Carbon dust drawings showing surgical procedures. Artist unknown. |

The technique began to

make its way to Edinburgh when Audrey Arnott (1901–1974), an artist based at

the London Hospital, visited Brödel

in 1932. On returning to England, she passed on the new technique to colleague

Margaret McLarty (1908–1996), a freelance artist who had originally trained

under Professor Dott. Hester Thom, a Canadian artist and another of Brödel’s students, was Dott’s personal

artist until 1939; she taught the technique to Clifford Shepley (1908–1980) who

was appointed as medical artist at Edinburgh University in 1934. The drawings

in the archive are by a number of different artists, including Thom and

Shepley.

|

| A carbon dust drawing showing a brain prior to impact with a wall, with coloured highlights. Artist: Clifford Shepley, 1960. |

Over

the coming weeks I will be rehousing these, to better protect the delicate

surfaces of the drawings and make them more easily accessible. The drawings are currently stored in folders in plan chest

drawers, one on top of the other. This has allowed movement within the drawers

as works were removed for production to readers, leading to some abrasion to

the surfaces and loss of gypsum at the corners and edges.

If you’d like to know more about these

unique drawings or the progress of the project, do get in touch!