|

| Page from one of the Royal Edinburgh Hospital 19th century Case Books |

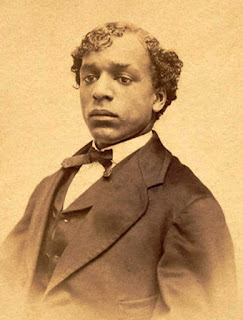

Edward Henry Hare begins his impressive 1962 article Masturbatory Insanity: The History of an Idea by stating ‘A hundred years ago it was generally believed by the medical profession…that masturbation was an important and frequent cause of mental disorder. Today no one believes this; and the masturbatory hypothesis (as we may call it) has in all probability been finally abandoned.’

"He was young, handsome; his mother's fond hope". This illustration is from an 1830 book titled Le Livre Sans Titre (The Book with No Name). The book concerns the perils of masturbation and includes a sequence of illustrations showing a young boy's descent into ill health due to his indulgence in 'self-abuse'. Images courtesy of Dittrick Museum.

The belief that there was a connection between masturbation and ill-health made its debut into Western popular culture after the publication of the best-selling book, titled (ready for it): Onania, or the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution, and All Its Frightful Consequences, in Both Sexes, Considered, With Spiritual and Physical Advice for Those Who Have Already Injur'd Themselves by This Abominable Practice (c. 1712 - 1716). As you may have guessed by the title, the book is, in essence, a cautionary tale. It is mostly comprised of moralistic admonishments, but the author does touch on how the ‘heinous sin’ of masturbation carries physical consequences as well, even possessing the potential to induce madness or epilepsy. For men, the loss of semen incurred from the act of masturbation would lead their offspring being born ‘commonly weakly little ones, that either die soon or become tender, sickly people, always ailing and complaining; a misery to themselves, a dishonour to humane [sic] race, and a scandal to their parents."

Michael Stolberg reflects in his article Self-Pollution, Moral Reform, and the Venereal Trade: Notes on the Sources and Historical Context of Onania that: ‘The work's original format was that of a moral treatise, which used medical arguments to support the basic notion that masturbation was a heinous sin against God and nature.’ The author of the book Onania does suggest some remedies and tinctures and a ‘prolifick powder’ for 12 shillings which could help the ‘Injur’d’s’ genitals recover from the ‘abominable practice’.

|

| 1756 edition of Onania. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection. |

The book was incredibly influential, even capturing the attention of eminent physicians like Samuel-Auguste Tissot who further proliferated information on the array of negative effects masturbation can wreak on the mind and body through his own 1758 book Onanism, or a treatise upon the disorders produced by masturbation.

Skip forward a 100 years and there’s a flurry of patients diagnosed with ‘Insanity of Masturbation’ within the Royal Edinburgh Hospital (REH) case books. You can find the majority of these cases within volume 15 (female patients) and 16 (male patients). These case books cover the years 1862 – 1866, coinciding with the period David Skae was Physician Superintendent of the REH. In fact, it was Dr Skae who was the first to maintain a specific type of insanity due to masturbation. Allan Beveridge wrote in his article Madness in Victorian Edinburgh that: 'Some of Skae’s categories, notably that of Masturbatic Insanity implied an aetiology that was debatable. In fact, although masturbation was repeatedly commented upon in the patients’ case notes, it was only occasionally used as a primary diagnosis.'

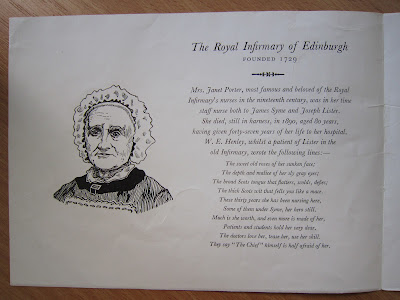

In his paper Of the Classification of the Various Forms of Insanity (1863), Skae describes the symptoms prescribed to the ‘masturbators’:

'...the vice produces a group of symptoms which are quite characteristic and easily recognized, and give to the cases a special natural history: the peculiar imbecility and shy habits of the very youthful victim; suspicion and fear and dread and suicidal impulses and scared look and feeble body of the older offenders, passing gradually into Dementia or Fatuity'.

|

| Portrait of David Skae (1814-1873) |

I have read all of the case notes relating to REH patients who were diagnosed with Insanity of Masturbation (IM). It has been an interesting experience, although often rather sad and perplexing.

It’s curious to note the differences in the descriptions of

the symptoms of the female and male patients diagnosed with IM. The women are

described as being extremely restless, talkative and sexually forward

(reminiscent of the symptoms associated with the once common medical diagnosis of Hysteria). In several instances,

the physician notes how the female patient would appear or act overly sexual:

‘Very salacious’

‘Expression very emotional, confused, sexual…’

‘…has an ugly lecherous smile on her face’; ‘The prurient expression of her face still remains’.

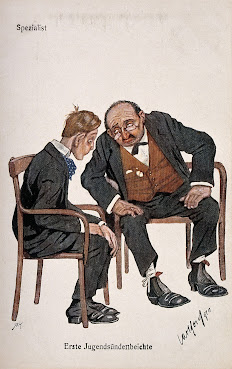

The male patients with IM however, are often described as taciturn, shy, physically weak, pale or ‘pasty’ with a strong aversion for making eye contact. There are a few examples of this description within the case books:

‘Pasty, unhealthy complexion…. Rarely looks at you when

speaking’.

‘His face is full and puffy, his complexion pasty and

unhealthy, his eyes watery and his expression nervous, scared and downcast. His

appearance and manner are strongly suggestive of a masturbator.’

‘This patient is a respectable looking lad, with a good,

intelligent face but with a nervous, restless, anxious expression. His eyes do

not look at you when he speaks but are constantly moving about and if you catch

them, they drop almost immediately.’

‘He is an unhealthy looking lad with a pale, pasty complexion and is much emaciated. Does not look more than 16. When this was remarked to him he expressed…that it was all due to masturbation: this he has been observed to be addicted to, to a frightful extent.’

|

| 'A gaunt adolescent consults a weary specialist'. Colour process print after C. Josef, c. 1930. Image Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection. |

This last patient recovered and gave up his ‘habit’ which the

physician believes made a marked difference in his appearance: ‘there is a

wonderful change in his appearance, is now stout, healthy looking boy with a

fresh, pleasant face’.

For one man there is noted 'this patient's insanity was attributed to masturbation but he himself denies ever having been addicted to this vice'. In The History of an Idea, Hare discusses the difficulty physicians faced in ascertaining whether a patient has masturbated or not, this he says, 'was solved on the principle of Morton's fork: those who admitted masturbation were believed, those who denied it were disbelieved'.

I was particularly interested in one female patient. Described as being a lady ‘of excellent education and steady industrious habits until her present illness’, her ‘insanity is to a very great extent dependent on her habits of masturbation.’ On her first admission she had shown some improvement ‘but relapses during the time of menstruation, when she behaves very stupid...’.

On this note, her menstruation, and the effects it has upon her person, is frequently remarked upon (which isn’t unusual within the case books):

‘Menstruation regular, habits very much improved; very bad woman when menstruating which is now the only time at which she masturbates’.

‘Sleeps very well except just before menstruation’

On her second admission the physician notes that he thinks she suffers from nymphomania.

There was one entry which I was rather shocked by:

‘Cauterization of the vagina has been tried, but with no good effect – previously her hands had been restrained at night by means of gloves; but although her bodily health certainly improved, no material improvement was noticeable in the mental symptoms. She also has delusions as to the identity of persons around her, and says her mind seems to enter the body of others.’

This is the first time I’ve come across mention of cauterization of genitals at the REH. I'm not sure why the procedure was performed in this instance - if the intention was that of preventing the patient from masturbating.

In the 1879 Manual of Psychological Medicine, there is a reference to cauterization as a way to prevent patients from masturbating: 'Blistering the prepuce we have found useful, but only for a time'. In the same excerpt, it is described how Dr David Yellowlees (who was the Physician Superintendent of the Glasgow Royal Asylum from 1874-1901) adopted 'wiring' as a treatment for male patients who masturbated: 'Dr Yellowlees rings the prepuce with silver wire, as the snouts of swine are wired to prevent their routing. The plan is ingenious and has been to a certain degree successful.' The author then adds 'In females even clitoridectomy has failed'.

|

| Isaac Baker Brown's The Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy, and Hysteria in Females (1866). Brown's thesis presented in this volume was that nervous affections complicating diseases of the female genitalia were the direct result of "peripheral excitement of the pudic nerve" or masturbation. Brown proposes clitoridectomies as a cure to these afflictions and performed numerous such operations on women until his career ended in scandal when it was revealed that many of his patients hadn't consented to receiving the procedure. |

%20Norman%20Dott.jpg)

%20Davrick%20Dunlop.jpg)

%20Dr.%20G%20Jamiason.jpg)

%20detail.jpg)