This post contains racist / offensive terminologies which were used during the period it discusses.

Celebrated for his poem ‘Invictus’, William Henley (1849 – 1903) also penned an unabashed racist portrait of a former student of the University of Edinburgh. After graduating, the student worked at the RIE as house surgeon while Henley was a patient there under Joseph Lister.

The student’s name was Dr George Rice and he had an extraordinary life and career.

As a teaching hospital, the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (RIE) has long held a close connection with UoE’s (University of Edinburgh) Medical School. As LHSA is based at the UoE Main Library, we are lucky enough to have the University’s heritage collections at a stone’s throw away from our own archive. One of the great things about the two archives neighboring one another is that we can easily trace former UoE student’s careers if they then went on to work at the RIE.

|

| Entry for George Rice in Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh Student Ticket Journal (alphabetical ledger of tickets sold to students for admission for clinical training) LHB1/16/55. |

|

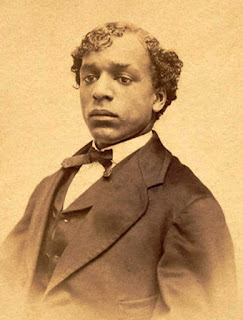

| George Rice within 'Graduates in Medicine' album, 1874. Edinburgh University Heritage Collections. EUA IN1/ADS/STA/8. |

Over the last few years, long belated moves have been made to reveal the stories of people of colour who attended Edinburgh University over the course of its history. Projects like UncoverEd have at their root a decolonising aim, with current students using the University’s archive to create a biographical database of students from Africa, the Caribbean, Asia and the Americas. These past students have had a role in the University’s history yet a long heavy silence has erased their contribution to its institutional memory. The UoE has long accepted students from all nationalities and ethnicity (the first known black student was Jamaican-born William Fergusson - he matriculated in 1809) yet the historical students we remember, who have had films, books, and articles written about them, are largely white (and male).

Two years ago, NHS Lothian made a commitment to fully

address how the Royal Infirmary benefitted

from its ties to the Atlantic slave trade. LHSA welcomed researcher Simon

Buck to the team, who has been sleuthing through our RIE archive investigating

and uncovering the often painful and shameful truths of how little was

untouched by the slave trade, whose profits left an insidious stain on Edinburgh’s

history. For its part, the Royal Infirmary inherited an estate in Jamaica from

a Scottish surgeon/slave owner in 1750 which the hospital still owned as late

as 1892. Included in this inheritance were 39 human lives (or the estate’s

slaves, later ‘apprentice’ labourers) who worked on it.

The Hospital’s links to slavery do not end there. The RIE

would receive thousands of donations and bequests, a considerable amount of which

was ‘blood money’ - or slavery-associated money.

There will be a series of public consultations on the RIE’s ties to slavery in the next month or so, to anyone

interested, please do attend.

|

| Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh - Copy of 'Inventory and Appraisement of the Goods and Chattels, Rights and Credits of the Late Archibald Ker'. Inventory includes 39 slaves, each listed with a name (given by slave-owner). LHB1/72/5/6a |

Simon recently asked us about BAME staff at the RIE and our Archivist, Louise Williams, mentioned a black American surgeon, Dr George Rice, who was employed by the RIE during 1870s. She had come across his story while researching an enquiry we received last year. Some fascinating research has been written up on his life and career which I will link below. Dr Rice’s story provides links between institutions with every repository holding a fragment of a puzzle which, when pieced together, provides somewhat of a full picture of his life and career.

George Rice was born in Troy, New York, and graduated from Dartmouth College Medical School in 1869. Rice’s father, a steamship steward, wrote to Dartmouth’s President Asa Smith: ‘He wants to be a physician and I shall assist him in all my power to be an accomplished one’.

|

| George Rice image courtesy of badahistory.net, Blacks @ Dartmouth 1828 to 1960 |

After being denied admission to Columbia University’s

College of Physicians and Surgeons, George moved to Europe to

continue his studies.

He was first based in Paris before relocating to Edinburgh

after the eruption of the Franco-Prussian war. He enrolled in Edinburgh

University in 1870 and graduated in medicine in 1874, thereafter securing the

position of House Surgeon at the RIE, working under renowned

pioneer of antiseptic treatment in surgery, Joseph Lister.

%20detail.jpg) |

| Mention of George Rice in minute of RIE Minute book 17th May 1975. LHB1/1/28 |

Serendipitously, my last blog post covered the nursing

career of Janet Porter, who also worked under Joseph Lister as his staff nurse

from 1869 to 1877. Undoubtedly, George and Janet must have encountered one

another on the wards of the RIE – Janet was described as being ‘esteemed by the

many students who came in contact with her’.

House physicians and surgeons were known as ‘residents’. As newly-qualified doctors, they would spend six months (at that time) working in the Infirmary supervised by a senior member of medical staff learning their ‘trade’. Although we do hold some records that feature residents, these do not say what life would have been like for them day-to-day, but are more like proof that they were there. But Henley's poem may give us an insight into Rice's experience of working at the RIE.

|

| George Rice (middle) during his time as House Surgeon at the RIE. Image from 'The Student' Vol V, 1901. Reference: EUA IN20/PUB/1 |

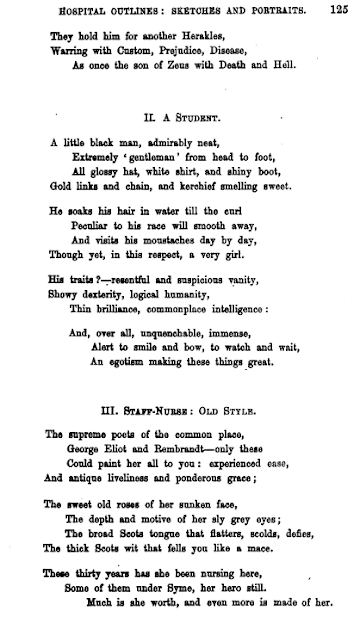

William Henley was a patient of Lister at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh from 1873 for three years. During his time as a patient at the RIE, Henley wrote some 28 poems and a few of these were first published in The Cornhill Magazine as Hospital Outlines: Sketches and Portraits. The poems are impressions of those around him; his fellow patients, the nursing staff in the process of professionalization, and the general atmosphere of the hospital. One of these portraits, a racist description of George Rice, exposes Henley’s own blatant prejudice.

The poem, titled ‘A Student’, was

published in the July 1875 edition of Hospital

Outlines in the Cornhill magazine and appears just above Henley’s poem of

Janet Porter titled ‘Staff Nurse – Old Style’.

|

| Racist poem in the July 1875 edition of Hospital Outlines in the Cornhill magazine |

‘A Student’ is missing from later

editions of the Hospital poems perhaps because of this letter written by

Lister to Henley in which he reprimands the poet for publishing ‘so severe a

picture’.

"It may interest you to see, if you have not already

done so, what is said of them by the paper of which I send you a copy. I may

add that it expresses very much my own feeling about them: they have surprised

and pleased me very much. Of one of your portraits it would not become me to

speak; but of another, that of 'A Student', you will I trust forgive me for

saying that I cannot help regretting the publication of so severe a picture. I

say this as your friend, because I sincerely hope with the Review that we shall

'hear again of' you as a poet; and I am afraid indulgence in this vein may make

you needless enemies of those whom you so sharply chastise. I rejoice that you

can report so favourably of your foot and quite hope it will soon be

sound."

George Rice appears to have held Lister in high esteem (he christened his son with the middle name of ‘Lister’)

and this sentiment seems to have been reciprocated. Within a certificate of recommendation written by Lister

and held by Sutton Archives, he comments on Dr Rice’s ‘exceedingly efficient

manner’ and ‘indefatigable zeal’ in which Rice went about his professional

duties, writing that Rice will go on to secure ‘a very high place in the

profession’. Dr Rice would indeed go on to have a brilliant career, eventually marrying

and then settling in Sutton where we would go on to practise medicine.

|

| Lithograph of Joseph Lister, n.d. |

|

| University of Edinburgh Journal 7, 1934/1935, p. 179. Rice is described as 'the last oldest survivor, with one exception, of Lord Lister's house surgeons in the Royal Infirmary.' |

|

| Dr John Chiene. Etching by W. B. Hole, 1884. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection. William Brassey Hole was the grandson of William Fergusson (the first known black student to enroll at UoE). |

In terms of context, the 19th century saw institutions across Britain

fuelling an imperial and colonial agenda which sought to justify the dominion

of whites over non-white people and advance racial inequality throughout the empire. This dogma would

creep into the research of the Victorian scientific

community with pseudo-sciences such as phrenology (Edinburgh was the principal centre for the study of phrenology in Britain at this time) and

polygenism gaining widespread influence. Outwith the scientific community,

there was a growing popularity of racist entertainment: human zoos and

international exhibitions (which included living exhibits of colonised ‘exotic

populations’) as well as popular shows involving blackface minstrelsy.

Back to Henley’s awful poem, I find the first two lines incredibly poignant:

A little

black man, admirably neat,

Extremely

‘gentleman’ from head to toe

I can picture Henley’s probing eyes scanning Rice’s appearance from head to toe. He picks apart Rice’s immaculate clothing, his hair ‘peculiar to his race’ which he ‘soaks in water till the curl will smooth away’.

The poet does his worst to insult Rice’s appearance while also dismissing the doctor's skill and intelligence (thin brilliance, commonplace intelligence). By doing so, he challenges Rice’s position at the RIE as a university-educated and promising young doctor.

Henley describes Rice as being overly concerned with his appearance ('visits his moustaches day by day'), effeminate ('a very girl'), and conceited ('suspicious vanity') - much like a 'dandy', or 'fop'. Wikipedia describes the dandy as 'a self-made man in person and persona, who imitated an aristocratic style of life, despite his middle-class origin, birth, and background'.' I get the impression Henley is implying that Rice is dressed above his station, performing as a member of white high society. This is evidenced by the way he sandwiches the title of gentleman between air quotes, sneering at what he feels are Rice’s attempts of emulating the garb of a Victorian gentleman.

Despite his ‘gold links and chain’, his ‘white shirt, and shiny boot’, and his prestigious degree from one of the world’s leading universities, Henley's glare shrinks Rice, reducing him to a ‘little black man’.

We don't know if Rice read this poem, or what he made of it. What we do know is what Rice went on to make of himself, building an incredible life and career.

For enquiries relating to past students at the UoE please contact the Centre for Research Collections Research Services team at: is-crc@ed.ac.uk

Further reading:Black Victorians: the hidden Britons who helped shape the 19th century. https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/black-victorians-britons-famous-who/

No comments:

Post a Comment