What are zines?

Zines are mini music-themed magazines that were originally created by members of the punk rock scene in the late 1980s and 1990s. These zines typically included music reviews, press releases and information on gigs, venues and musicians. Once produced by hand, the zines were then Xeroxed and distributed within the community for a small fee, or if possible, for free. The punk ethos tied to zine production separates zines from other forms of self-publishing because, in contrast to their traditional self-publishing counterparts, zinesters (people who make zines) do not wish to participate in corporate or mainstream publishing and they do not want their product to come out looking like a book from a traditional publisher. In fact, in contrast to most writers, zinesters often choose to reject offers from corporate publishing houses. Therefore, people who create zines are not only people who have been relegated to the margins, but also people who have chosen to claim the margins. This insistence on claiming the margins is due to punk culture’s Do It Yourself (DIY) ethic, which is also reflected in the DIY aesthetic of zines.

|

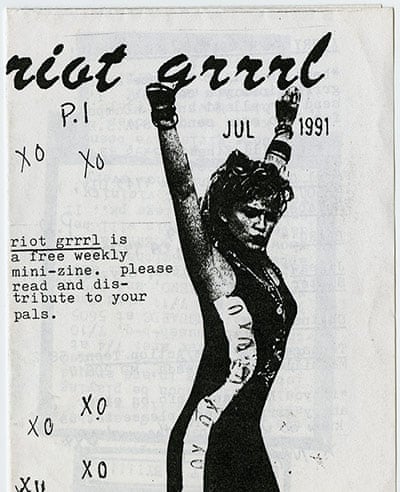

| The cover of a riot grrrl zine from 1991. |

Who makes zines and why?

Zines were written by marginalised people who were often young and economically disadvantaged, and whose ideas fell outside the mainstream. People who were under- or unrepresented in the mainstream media worked to document the voices of those too politically radical to appeal to the corporate media through the production of zines. The most famous and influential zines which remain in circulation today are those from the riot grrrl movement. The riot grrrl movement comprised of a group of smart angry women who emerged from the punk scenes in Washington during the early 1990s. These women went to punk shows, took photographs, read feminist books, wrote essays on the “male gaze”, and developed fierce life-changing friendships with each other. As a movement, riot grrrl was established in direct response to sexism in the punk scene, calling for the liberation of young women by taking control of the means of subcultural production and, in pointed contrast to mainstream - and underground – culture, sought to unify women and to revivify feminism. The movement achieved this by encouraging women to play instruments, start bands, share experiences in the safe all-girl spaces of the riot grrrl meetings, and most significantly, to write and distribute zines.

What do zines have to do with archives?

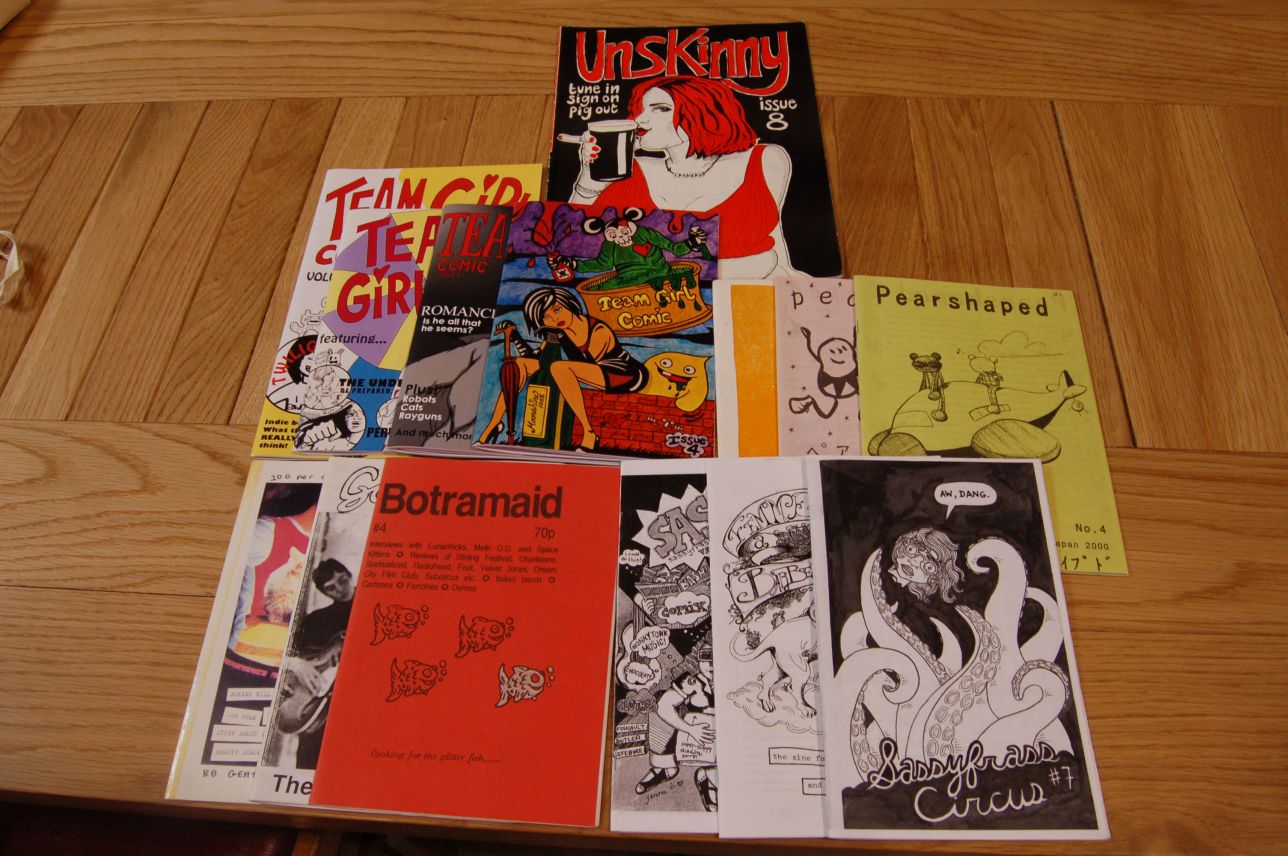

By producing zines during and about the riot grrrl movement, the riot grrrls created ephemeral feminist materials that documented their experiences in their own terms. In collecting and preserving these zines, which are now considered primary sources, feminist archivists are able to firmly place the riot grrrl movement into the historical record. The most well-known archive to hold feminist zines is The Fales Library & Special Collections in New York. Lisa Darms, who was a riot grrrl in Olympia during the 1990s, and is now an archivist, created this collection of zines, called the Fales Riot Grrrl Collection, in order to document the riot grrrl movement of the years 1989 to 1996. To see some zines locally, Glasgow Women’s Library and Glasgow School of Art Library hold a large collection of zines in their archives. If you'd like to make zines with me, you can do so at two feminist zine-making events that I'm running for LHSA on the 20th February and 22nd February 2017.

|

| A selection of zines at Glasgow Women's Library. |

So, what did we make?

We made two things! First: my colleagues at LHSA, who had never made a zine before, sat down together to make a zine each. The zines did not have to follow any specific theme, so everyone picked their own topic, and, armed with glue, old magazines clippings, pens and paper, everyone went forth and created a zine! I think the results are really stunning:

After our zine making session, I made a zine which can be read online, about our favourite items in LHSA's archive. Read it below, and make sure to open the zine on full-screen mode so that it's legible:

To read more of LHSA's digital publications click here.

To read more of LHSA's digital publications click here.