This week, we have had to say farewell to Employ.ed intern, Carmen, as her placement comes to an end and she takes some well-deserved time off to enjoy the summer. Having Carmen with us has been a pleasure - not only has she embraced her task to compile a resource around the history of bio-engineering in Edinburgh (and finished her internship with considerably more knowledge about the subject than the rest of LHSA staff), but she has also approached every task she has been asked to complete with genuine enthusiasm. All that's left is to wish Carmen the best for her final year at University and her career ahead!

I have been working as a Bio-engineering Archive Intern with LHSA for ten weeks now, and my time at the Archive is now sadly coming to an end. I have had an absolutely phenomenal experience this summer and have loved learning about a whole new branch of medicine which I previously knew nothing about.

As part of my internship, I have been involved in creating an educational online resource about the bio-engineering industry in Edinburgh from the 1960s until the present day. As I mentioned earlier, I knew nothing about the history of bio-engineering at all before starting this internship; however, my desired research area is medical social history and the history of disability, and so I was very enthusiastic to learn. I spent the first few weeks of my internship increasing my understanding of the collection – so a long time looking through various boxes and files! – and narrowing down a few topics that I found the most engaging to discuss in my resource. I believed that it was extremely important to include the stories of David Simpson and David Gow, the pioneering medical professionals involved in developing various powered prostheses; the history of the Bio-engineering Centre where all of these developments took place; and how this in turn impacted the lives of the patients that they supported.

As a History student, I found learning about a new topic that I might not have learned about during my degree extremely exciting, and I was pleasantly surprised by how much knowledge I had gained through my independent research in such a short space of time. As part of my internship, I was also extremely fortunate to have the opportunity to meet David Gow and conduct an oral history interview with him. This was beneficial in enhancing my knowledge about the history of bio-engineering in the city, as it meant that I was able to hear a personalised account from someone who had been a key figure in the industry. It also meant that I was able to record and catalogue the testimony for the Archive, benefiting researchers who want to study this topic in future.

I was pleasantly surprised by the collection – I was a bit terrified that there would be hundreds of extremely technical engineering diagrams that, with my History background, I would not be able to understand! However, while there certainly are diagrams like that for those interested in understanding and interpreting them, there are also many parts of the collection that give us a glimpse for what it was like to be a patient at The Princess Margaret Rose Hospital (PMR) receiving treatment at the Bio-engineering Centre. In 1966, the PMR opened the Self Care Unit, where children with upper limb deficiencies would stay with their mothers while they received treatment. Around four or five families stayed at the Unit at the same time, meaning that the children forged close bonds with one another.

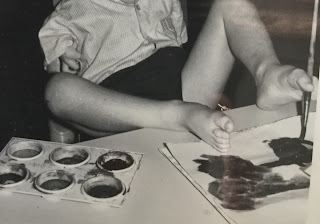

One of my favourite documents is a patient album compiled by Helen Scott, an occupational therapist at the PMR. In the album, it is clear that Scott and other occupational therapists assisted children with upper limb deficiencies, including those affected by the thalidomide tragedy in the 1960s, in learning how to navigate daily tasks such as eating, dressing and going to the bathroom independently. In the files, it often mentions that parents were recommended to modify clothing (for example, using Velcro instead of buttons) for their children to make it easier for them to dress themselves. This document was extremely useful to my project as I gained more insight into both how intensive the therapy sessions for disabled children could be, and the encouragement that the children were given to be as independent as possible. Furthermore, I also learned that while some children chose to wear a prosthesis, there were also some who did not, preferring to use their feet instead. This brought home to me the importance of the Bio-engineering Centre, as the introduction of this department meant that patients had the choice as to whether they used an artificial limb or not.

Another one of my favourite elements of the collection is the diaries written by David Gow from 1981 to 1984. After Gow graduated with a degree in Mechanical Engineering from Edinburgh University in 1979, he soon began to work at an electrical engineering firm called Ferranti, where he kept daily written accounts of his work. This was a custom that he continued when he first began to work at the Bio-engineering Centre as a Research Associate in 1981. I really enjoyed reading these diaries because I think that they are a rare opportunity to see the beginnings of David Gow’s career, which is all the more fascinating because he has contributed to transforming the field of artificial limb design with his creation of the i-limb hand, the first ever artificial hand to have individually articulating digits.

After I had decided which areas of the collection I wanted to cover in my resource, I then started researching what was the most effective way to display my information so that it was engaging and accessible. I came across an online platform called Prezi, which is normally used to create interactive presentations. I thought the layout of the platform would be extremely useful in allowing me to create an interactive resource which would allow people to click on topics they were interested in and interact with the resource at their own pace. In order to make the resource as accessible as possible, I also researched what kind of colour schemes and fonts were the easiest to read for those with learning disabilities, which then impacted how I would choose to design my online resource. This was one of my favourite aspects of my project as I felt very supported and encouraged to take initiative and make these decisions by my colleagues at LHSA. It also meant that my resource can reach as many people as possible; as someone who desires to work in cultural heritage to ensure that everyone can learn more about their history, this is an issue that I am extremely passionate about.

My internship also allowed me to learn more about the diverse work carried out by LHSA. For example, I had a day where I worked with Louise Neilson, our Access Officer, on enquiries sent by those looking to learn more about their family history. I found this extremely enjoyable as it showed me the sheer wealth of enquiries that they receive on a regular basis and the amount of time and effort that goes into helping with each one. I also got to help out with the first ever LHSA Showcase – this was an event in which LHSA invited academics with a particular interest in health to look at our collections to encourage them to use data from archives in their research.

As well as encouraging academics to use the collections, I had the chance to see the public outreach events activities of LHSA by attending community workshops and a creative writing class using the collections as inspiration. All of these events were a great success and further highlighted to me that the Archive does so much more than cataloguing (even though this is essential work!); they also work very hard to ensure that both the public and researchers feel comfortable to contact them and access their collections.

Overall, I am very proud of the resource that I have created as part of LHSA, and am very grateful to the team for allowing me the opportunity to be creative and improve my project management skills. This has made me realise that I should be confident in my own capabilities, which will certainly help me in my studies and in future work. I am very sad to be leaving but I look forward to seeing what else such a fantastic organisation has in store!

You can see Carmen's resource here: https://bit.ly/33rnT9R. In the meantime, here are some of her favourite images from the collections:

You can see Carmen's resource here: https://bit.ly/33rnT9R. In the meantime, here are some of her favourite images from the collections:

A patient at the Princess Margaret Rose Hospital painting

using their feet. Taken from Helen Scott’s patient album, c.1960s/70s.

Archive Number: Acc10/001/A Selection of Children with

Congenital Upper Limb Deformities who attend The Self Care Unit for Assessment

and Training.

A page from “Clothing for the Limb Deficient Child”, 1968, Acc10/001. This was written by Aline K. M Macnaughtan, then Head Occupational Therapist at the PMR. On this page, Macnaughtan recommends that dresses have Velcro fastenings so that they can be taken on and off easily, even when wearing prostheses. It also mentions the importance of having enough space to hold a cylinder of carbon dioxide. This is because during the 1960s, Professor David Simpson, then Director of the Bio-engineering Centre, was renowned for making pneumatic (gas) powered artificial limbs because he believed that this was much lighter for children to use than the long-lasting batteries available at the time.

An entry from David Gow's diary, June 1983, Acc10/001. Gow began to have a work diary whilst working at Ferranti and it was a practice that he continued whilst working at the Bio-engineering Centre. This entry in particular discusses fitting a patient with an artificial limb. Personal names have been redacted. The diary entry reads as follows:

"10th June

Bill and Paddy are experimenting with fabricating a socket for [patient name].

Converted the OttoBock (scrap) hand for the hydraulic link jig took shaft through from motor piston (motor in housing) and fixed bevel gear to it.

Powered motor. Sufficient power to operate the hand from the link. Alignment of bevel gear seems to be critical and although it is possible to drive ma motor it is not possible to drive just by using hydraulic link.

Taking socket out [patient's home] to see if it fits.

13/6/83

Socket is perfect for length. Cap needs remade - bone becoming prominent. Cap being strengthened and beefed up."

No comments:

Post a Comment